This article was originally posted on the Blog of the American Philosophical Association. We bring it to you as part of our new “From the Archives” initiative, highlighting selected works from the APA’s outstanding philosophical community.

You can learn more about the APA and its work here.

Introducing foundational ethical theories can be a dreaded task for instructors; thwarting off cultural relativism and fielding questions such as “Yeah, but does this REALLY matter?” However, I am always excited to have the opportunity to challenge my students, most of whom have never taken a philosophy course before, to evaluate their deeply held convictions and try to make sense of how we deliberate about moral issues. Further, my classroom is an active space; I treat my classes as places to learn together and with each other through a variety of activities. Not only is it fun for the students to work through dilemmas together, but, as an instructor, it pushes me to expand my pedagogical horizons and find interesting and exciting ways to incorporate games, puzzles, and challenges that breathe new life into the material I cover again and again.

Enter: the escape room. Traditionally, escape rooms are (paid) immersive experiences where you and a group of friends (and/or strangers) are tasked with a mission that involves multiple physical rooms. In each room, you are given a certain time limit to solve clues, puzzles, or accomplish tasks to “unlock” the subsequent room. If you fail to do so, you do not move on in the challenge, which leads to “failing” to “escape.”

Since I do not have the budget to bring all of my students to a local escape room, or, create a physical multi-room activity, I scaled down an escape room to fit within the space and resources available to me in my classroom. While designing my unit on Utilitarianism, I luckily had a conversation with an academic acquaintance about combining an escape room framework with class discussion. However, I then took this idea and ran with it, ramping up the discussion framework to multiple hands-on puzzles. We all love a discussion of the trolley problem and the good old organ donor debate, but having students work hands-on with these problems makes them more tangible, and honestly, who doesn’t love a little friendly competition?

The Escape Room Simulation

Once the escape room seed had been planted, I was running wild with ideas. To organize my thoughts, I consulted the (controversial) ChatGPT website, which assisted in providing an outline for the rooms. However, as there are significant limits to ChatGPT, I used the basic structure to flesh out the details and puzzles for each room, drawing on the material we had covered in class. Prior to this activity, students had read and discussed in class selections of John Stuart Mills’ Utilitarianism (from Rachels & Rachels The Right Thing To Do: Basic Readings in Moral Philosophy) and a fictionalized challenge to this view: Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from the Omelas.” In this story, Le Guin describes a utopian society and later reveals that the happiness conditions for the citizens depend on the suffering and torture of one child held in a dungeon.

In small groups and as a class, we discussed the main tenets of Mills’ utilitarianism, and how Le Guin’s story provides a unique critique of the greatest happiness principle. Then, I ran the Escape Room activity. Before students entered class, I divided the room into 4 “Escape Rooms” (tables) with a large envelope labeled “1.” At the start of class, I let students know that we had now entered the Omelas Escape Room. To successfully escape by the end of the class period, they must work together to solve the problems, riddles, and puzzles they are presented in each “situation room.” In front of them, was the first situation room. Once they had solved the dilemma and/or puzzle, they would bring it up to me. If they were successful, they “unlocked” the next room and received the subsequent envelope, signifying they had “moved ahead” in the escape room.

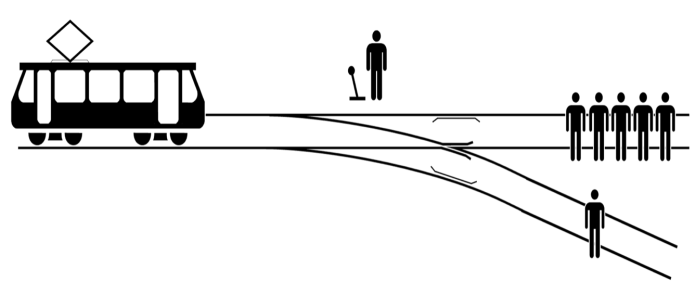

Situation Room #1: The Trolley Problem

The first room focused on the trolley problem. In the packet, there was an envelope with 6 tokens (small beads), a brief description of the dilemma and the instructions for the room, and a visual printout to interact with. The tokens represent Happiness for each individual. Students were instructed to distribute the tokens so each person is represented by 1 token (Track 1 will have 5 tokens to represent the 5 individuals on that track; Track 2 will have 1 token to represent the 1 individual on that track). Then, as a group, they had to decide whether:

Option 1: Do not pull the lever and let the trolley continue on the path killing the 5 people. Remove the 5 tokens from the board on track 1. One token remains on track 2, as the 1 person’s happiness was preserved.

Option 2: Pull the lever, diverting the track and killing the 1 person. Remove their happiness token and keep the 5 tokens representing the 5 people’s happiness on the board.

They were instructed to write their answer and explanation on the note card labeled “1,” making sure to include how their group decided which track should get to preserve their happiness, and what moral theories they drew on to make their decision.

Figure 1. Trolley Problem

Then, students had to return the token(s) to the appropriate places on the board (1 token on track 1, 5 tokens on track 2). For the second portion of the dilemma, they were given the following scenario to consider:

Track 1: The five people are elderly and near the end of life.

Track 2: The one person is a child.

Again, as a group, they had to decide whether to pull the lever (removing the corresponding tokens), as well as what motivated their answer. Once they had settled on an answer and written it on a notecard, one student brought up both notecards and the packet and was handed the 2nd packet, giving them clearance to move forward in the simulation.

Situation Room # 2: Organ Donor Dilemma

Along the lines of the classic organ donor dilemma, students are given the following:

You are a transplant doctor. Five terminally ill patients urgently need organ transplants. One day, a healthy patient, Mr. X comes into your clinic for a checkup. It turns out that Mr. X is a perfect match for all 5 recipients. However, he is not at risk of dying. However, you could painlessly end his life in order to utilize his organs for your patients.

You are responsible for making the decision whether or not to kill Mr. X to transplant their organs to the 5 patients.

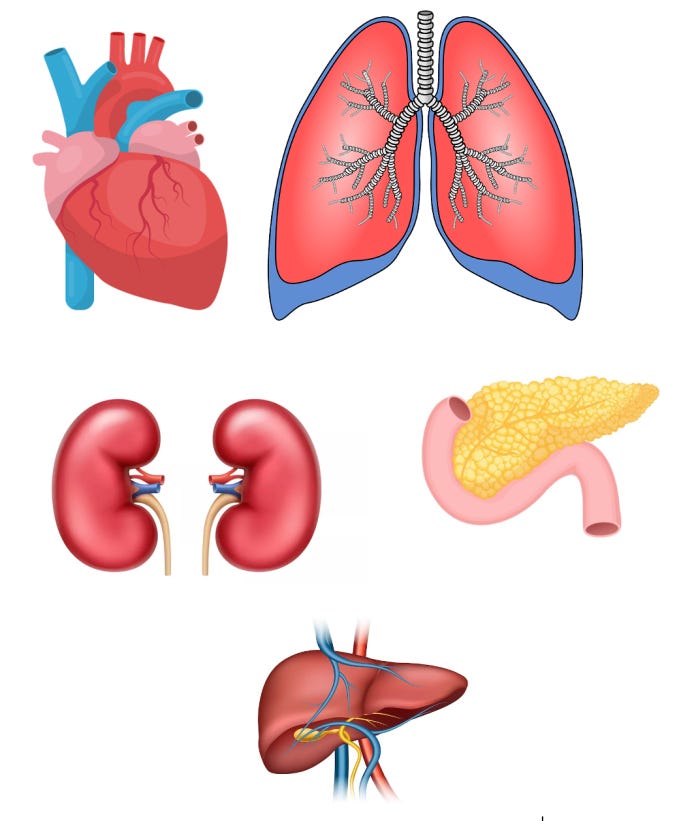

For this situation room, students are provided with:

5 notecards of individual patients describing their conditions

5 notecards displaying the organs needed (Heart, Lungs, Liver, Pancreas, and Kidneys)

There are 2 notecards labeled “Solution to Puzzle” and “Solution to Dilemma”

First, as a group, they must match the patient notecards to the corresponding organs (see Fig.2).

Figure 2. Index cards of the viable organs (L), index cards of the potential patients

Then, as a group, fill out the 2 notecards provided to them. On the “Solution to Puzzle” notecard, match the patient to the corresponding organ they need. On the “Solution to Dilemma” card, as a team, decide whether it is ethical to sacrifice one healthy person to save 5 people. In their answer, they were asked to consider: 1) how a utilitarian would answer and if the utilitarian perspective influenced their answer; and 2) would their decision change if the one healthy person was an objectively bad person (such as a serial killer or terrorist) and the 5 people were all living lives dedicated to helping others? Or what about the other way around (if the 1 person was “good” and the 5 people were “bad”). After a consensus was reached and the puzzle correctly solved, the team was advanced to room 3 and provided the following packet.

Situation Room #3: Pandemic Dilemmas

In this room, students are provided the following scenario:

A deadly, highly contagious virus has spread across the globe, and a limited number of antiviral doses are available. These doses can cure the infection if administered in time, but they are scarce. Your group of decision-makers must allocate the doses in a way that maximizes the happiness and well-being of society. In line with utilitarianism, the goal is to minimize overall suffering and maximize the well-being of the population.

However, the dilemma lies in choosing who should receive the doses:

Option 1: Healthcare workers on the frontlines, who are treating infected patients and preventing further spread of the disease.

They risk exposure every day, saving lives, and their health is crucial for treating more patients.

Without the cure, their death or illness could lead to the collapse of the healthcare system.

Allocating doses to them maximizes indirect happiness by protecting those who save others.

Option 2: Elderly patients who are more vulnerable and likely to die without the cure.

Elderly individuals are at a much higher risk of severe complications and death from the virus.

Their families and communities will experience profound grief if they die, causing significant emotional suffering.

Allocating doses to them maximizes immediate well-being by preventing loss of life in a vulnerable group.

Option 3: Young, healthy individuals who have a lower risk of dying but represent the future of society in terms of productivity and social well-being.

Though not at the highest risk, young people are the future contributors to society.

By keeping them healthy, society ensures that its future workforce, leadership, and caretakers survive.

Allocating doses to them maximizes long-term happiness by securing future productivity and social stability.

In order to “unlock” the key to the next room, students had to:

First, complete the word scramble provided in the envelope, which includes words that are important to the scenario. (See Fig. 3)

Then

Should the doses be given to the healthcare workers to ensure the continuation of treatment for others, the elderly who are more vulnerable, or the young individuals who represent the future of society?

Make sure to include—what influenced your decision and why did you choose the group you did?

If the word scramble was correct and the dilemma “solved,” the group was moved into the final room, where they were thrust into the city of Omelas.

As each clue was solved, they were provided with the following key (an envelope with a particular symbol) which unlocks another area of the map. Continue solving clues at different locations to reveal more of Omelas. The 3

“Now that you have discovered the truth about Omelas, will you stay and accept the happiness built on the suffering of one child, or will you walk away from Omelas, knowing you are leaving the happiness behind?”

Once the group has reached a consensus and turned in their answer, they have successfully escaped!