2024: A wonderful day in the neighborhood

There is a lot of despair in my society at the moment, which I attribute to the selfish ones becoming normative in United States culture. One of the most common things people bring up in passing talk, texts, and even when opening up over lunch or late at night is what to do. How can faith in human relations be restored from out of the toxic muck of cynicism in which so much of society has been sunk? I am not the kind of person who walks around with answers, but I do have one for that desperate question: try neighborhood philosophy.

By “neighborhood philosophy,” I mean philosophy done in or as a neighborhood, not philosophy about the neighborhood. Of course, philosophy done in the neighborhood often concerns the neighborhood, including what it means and what and where and who it is. That philosophy also can be out and about in the neighborhood. But I am not pointing to a theory of the neighborhood as the primary meaning of “neighborhood philosophy.” I am pointing to something formal about the way the philosophy is done – and lived.

That said, there are assumptions, of course. Neighboring is a social-ecological condition, if I may put it like that, where a good part of the sociality is moral. By virtue of living together outside the intimate realm of homes (however one defines those), neighbors have repeated occasions to engage in the basic interpersonal obligations that comprise being socialized people at all. This proximity of life shared leads to qualitatively more involved, sometimes contentious, often thickened relationships outside the family and lone self. Neighboring involves deepening moral relations around matters of local ecology in the broadest sense, much of which involves the human ecology of political economy.

But neighbors need not only be humans. Or at least the question arises whether the other-than-human beings that live with us might also be conceived as neighbors, oftentimes non-reciprocal, strangely communicative and off in their own worlds, yet also keenly aware of us, responsive to our interventions and offerings, and so on. In this spirit, my partner and collaborator on several projects, Misty Morrison, began noting the botanical neighborhood of our home. The multi-species justice scholars in our lives reminded us of the more than human home shared by many beings that involves both domestication and wilderness always inside and around it as life roils and strives.

The neighborhood is the location of neighboring. The location is socio-ecological as neighboring also is. But we should not rule out the notion of virtual neighborhoods or of other forms of temporally or spatially dispersed neighboring nonetheless located in specific ways through our technology and Earthly conditions. Still, given how important body language and day-to-day meeting in person is (including seeing people going on their way when they are not presenting to you directly (or even to anyone), I favor the location being non-virtual, spatially contiguous in a manageable way that allows getting around on foot, by wheelchair, or with a bike out and exposed to others in passing. I prefer locality permitting and admitting layering of memories from year to year, sedimenting, weathering, forming, coalescing into stories and deeper-level-feels about a place.

In that spirit, neighborhood philosophy takes place on the block. So it was, then, that Misty and I offered up some neighborhood philosophy at the 2024 block party. Our neighbor, Laura, had organized folks and invited everyone interested to her front lawn. While sitting there, the question came up of how we might contribute to the party for the neighborhood.

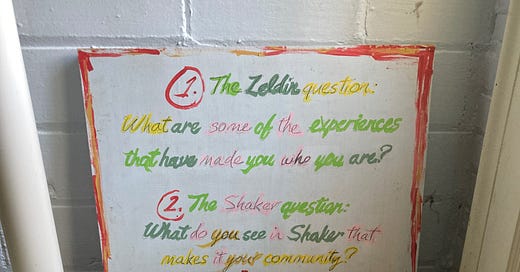

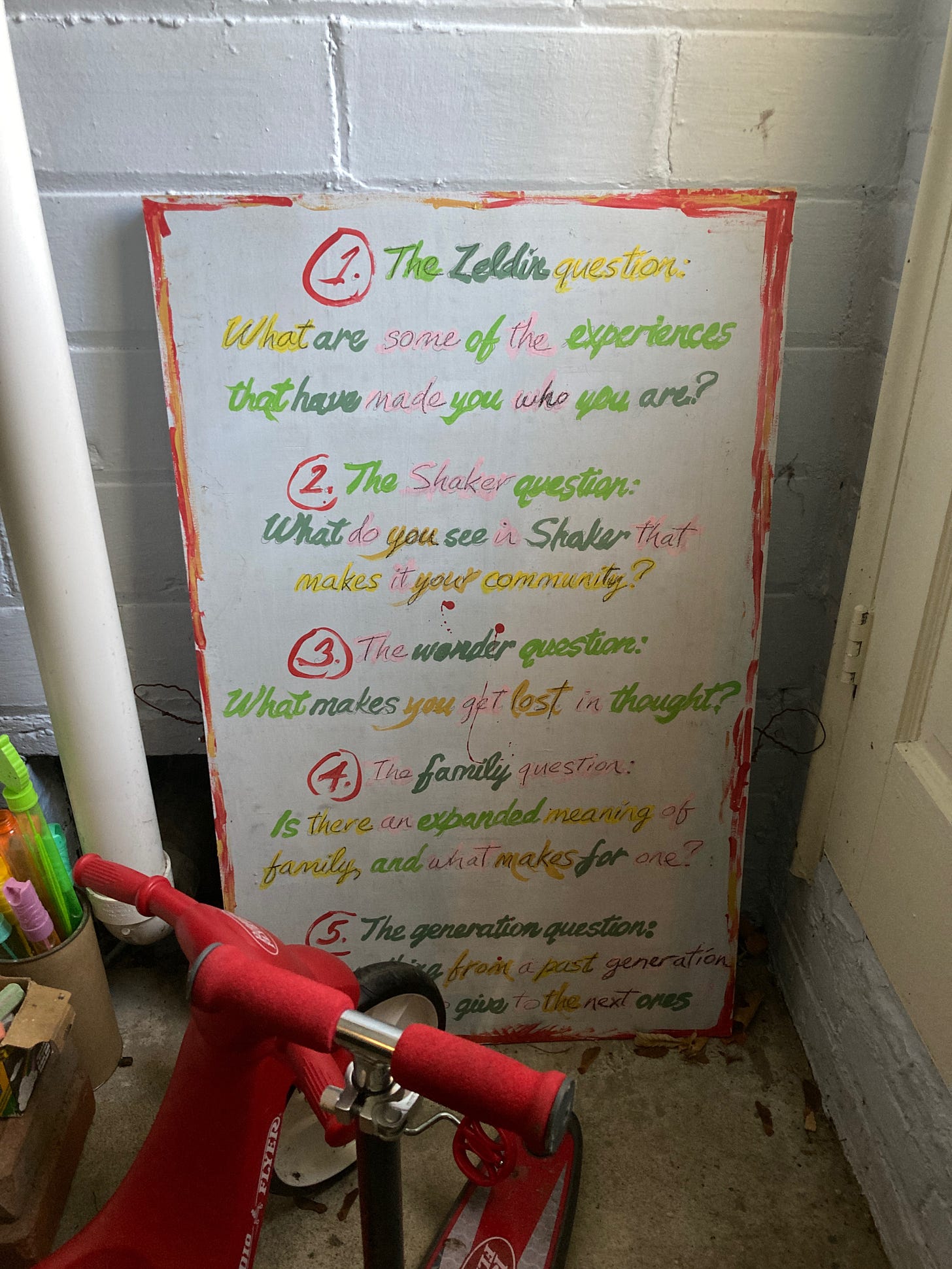

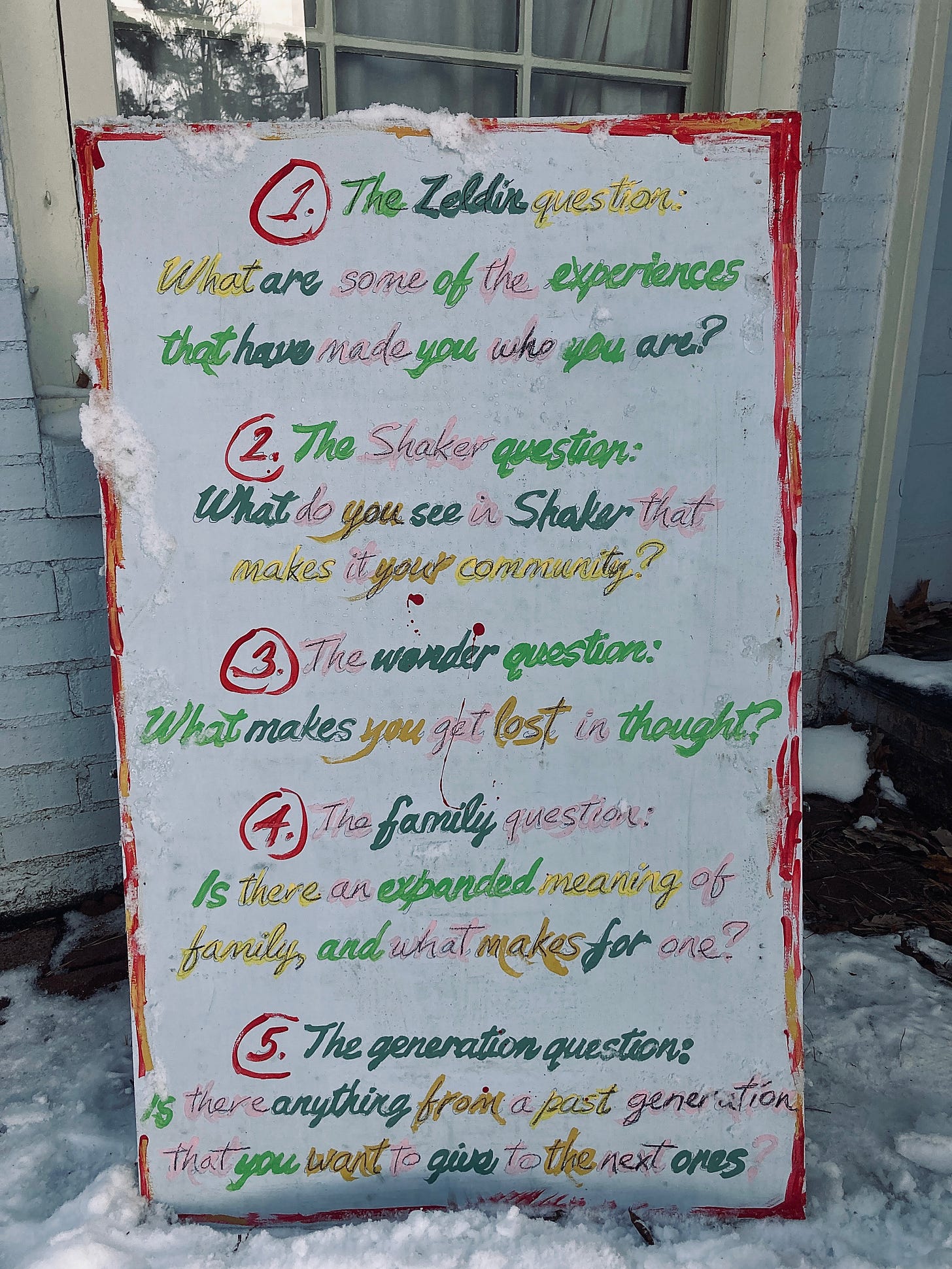

Talking things over in Misty’s studio one night after the kids went to bed, Misty and I created five questions as a basis for discussion among neighbors. Our inspiration came from Theodore Zeldin’s Oxford Muse discussion dinners of the 2000s. I had worked with Zeldin in the mid-2000s on portraits from the United Arab Emirates (they are astonishingly deep!). So, the first question was named after him, “the Zeldin Question.”

Well, what are they (re. question #1)? To them we added a question about our city, Shaker Heights, where we are proud of our community, tough though it is to form and keep a place that is idealistic and practical at once. Misty and I then added a question on wonder related to our book on that topic. A question about family followed, since families are such an important part of where we live. Finally, since there are so many kids on the block, we finished with a question about generational wisdom and transfer.

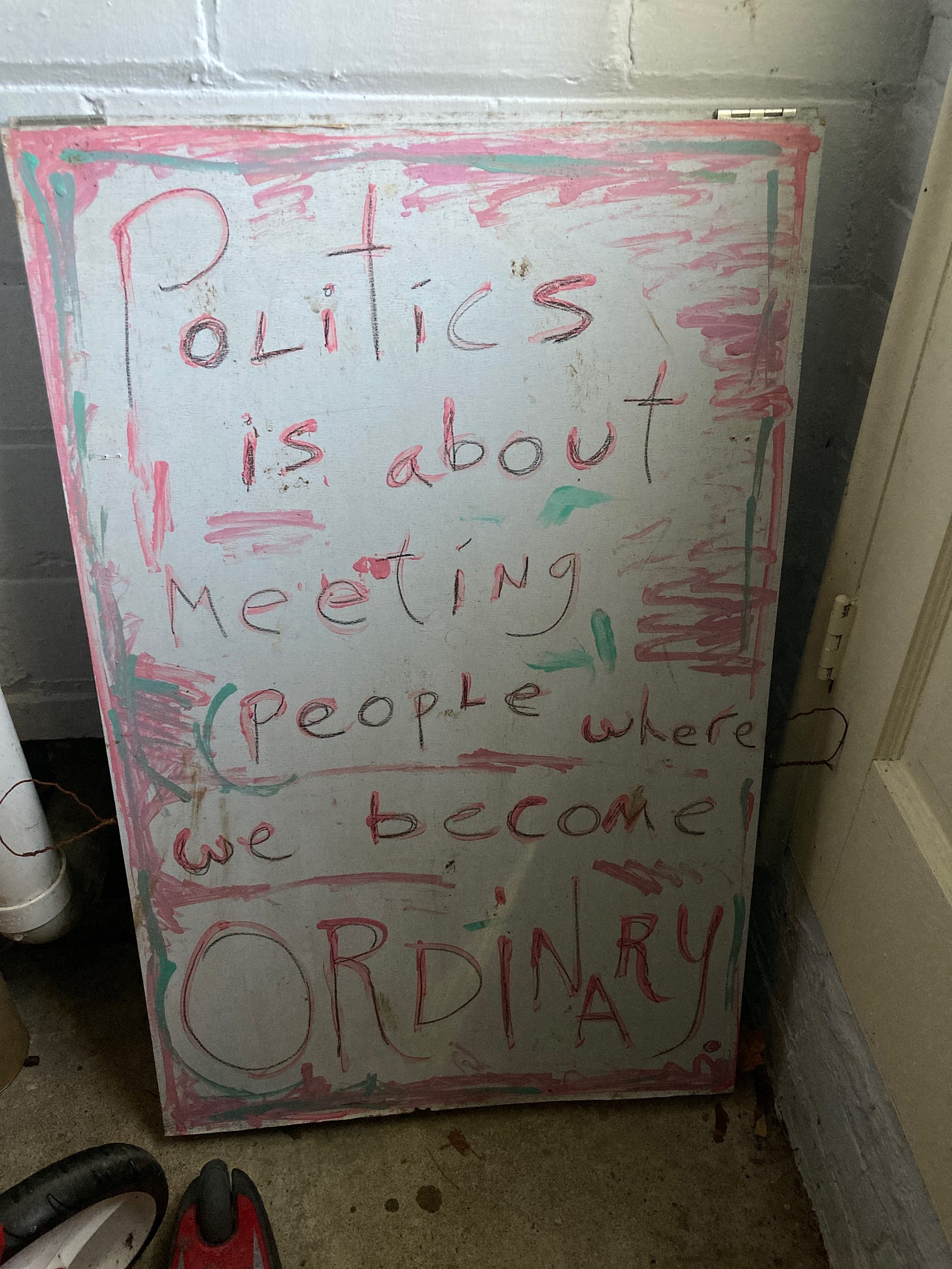

The idea was to ask broad, inviting questions that, when discussed, could lead to complications and the opportunity to civilly work through areas of discomfort. The questions were intended to help people grow in small ways, should people want that. They were also meant to broach politics from the apparently unpolitical, to ease into questions of how to govern our lives together. As a result, the questions were painted on a poster board the other side of which had a controversial saying:

What that saying means and whether it could be true was left hanging in midair. But in the context of 2024, the B-side of the question board displayed a commitment to non-spectacular and non-polarized politics beginning from interpersonal relationships rather than from impersonal platforms and issues. It nodded to social media and the ways in which the performance culture of virtual self-styling seeks extraordinary moments and personae. People in the board’s sloppy, even goofy, projection of community became ordinary through talking together. Kid stuff – on a block with lots of kids.

Neighborhood philosophy discussion began during the block party, but only minimally. People enjoyed the board and chatted a bit about it but were shy. We decided to hold a focused get-together in Misty’s studio in our basement later that Fall, based on the expressed interest of about half a dozen of our neighbors. Meanwhile, the board stayed in our front lawn by the walk, and people often stopped to look at it and think over the Fall – sometimes walking their dogs, walking with friends, or just passing by.

Finally, in early December, we held the meeting, and the eight or so of us gathered in Misty’s studio, the place where she does most of her painting and printmaking design and where she and I also collaborate on quilts that we make together out of old fabric that has a meaningful history.

We stayed until late in the evening when people with sitters had to return home. We got to know each other better and now have that conversation in the background of our shared memories and capacity to relate. Neighborhood philosophy, in this case, meant questioning together free of big heavy jargon or academic baggage, but open to fragments of it – like patchy quilt squares. The neighborhood philosophy meeting went well.

In past years, before I was a dad, I used to organize discussion groups, too. These forms of neighborhood philosophy met in easy-to-reach places: a local bookstore or a common room at the university. They involved a lot of evolving discussion on issues of conscience to those who attended over the weeks, coming in and out over the years. They were a form of public philosophy as emergent learning. Again, they suggested that reasoning can be a loving relationship between people and that love can be neighborly and Platonic, not charged and romantic. In other words, they were versions of neighboring in a locale that was not as rooted as found in my neighborhood in Shaker Heights where the neighbors live together on the block most of the time. The neighboring happened around a table in the basement of a bookstore over half a decade. When you ran into those folks outside the bookstore later, you remembered each other. You meant something to each other. The shared philosophizing was a real yet subtle connection, an invitation to view the world for its possibilities thoughtfully considered. To be careful in the best sense.

Quilting as a form of practical faith

Given the circumstances of my home, I am tempted to draw an analogy between the quilting we do and neighborhood philosophy. It’s the substance of this analogy that gives me some faith in this selfish and terrible time. Quilting is an art where one aims to make something comfortable for others, often with the very material of others or of the community upcycled in the process.

Quilting takes time. It is patient work. It is quiet, although one often talks during it or listens to music or podcasts. The house’s animals sleep on parts of the quilt while you are at work on it. The patterning is a way to think about reorganization, beauty, symbolism, and bodily comfort all at once.

The analogy with neighborhood philosophy is this: coming to get to know your neighbors is a kind of patient, quiet, thoughtful work that can end up being domestic, fun, and comforting. The philosophy is the thought that goes into stitching patches – or squares – together. It happens in a back and forth with your environment, figuring out where things came from, what they meant, how they go together – or don’t go together – and how to make something functional that is also beautiful. Quilting, like philosophy, aims broadly at flourishing and its conditions. We people are not quilt squares but are the stitchers of a collective quilt, the squares of which are patches of our contiguous living.

From the blog (backstory 2020-4)

In 2023, Sidra Shahid, Katherine Cassese, and I finished our joint project, Into Philosophy. It was a series of mini-series, with each of us taking the helm of some of them. One of mine was Philosophy as a Way of Life. The idea behind that mini-series was partially to expand the conventional understanding of that tradition unofficially begun by Pierre Hadot, so that it included, for instance, anti-colonial work, institutional change in our profession, non-academic community engagement by artists, and outdoor philosophy. At the same time, I wanted to relay some of the more traditional work in the area as expressed through the University of Notre Dame project on philosophy as a way of life during those years including its religious and non-Western dimensions.

The wider context for Philosophy as a Way of Life was Into Philosophy, and its main preoccupation, if I may summarize my interpretation of the joint endeavor, was to thicken philosophical discourse interpersonally so that we conveyed practices of philosophy that involve the whole person and adult relationships. None of us shied away from intellectual rigor, but each of us sought philosophy that is not gimmicky, not exclusively theoretical, and that has its place in reflection on how to live well. Conversation, not theory, was our preferred manner—everyday talk involving challenging ideas. The idea was to reclaim the experience and practice of reasoning as a loving relationship between people.

About eighteen months after Into Philosophy’s conclusion, I took up philosophy as a way of life again on the other side of that project – this time writing about democracy as a way of life. My goal in starting the new series was to continue to emphasize the broadening of philosophy to include ordinary and lived dimensions of philosophy that involve living democratically. I still want to thicken the tradition and make it almost unrecognizable from people extending philosophy into the weekend drives of their lives. I understand this life as a social one, involving the opportunity, joy, challenge, and task of living well with others as equals with whom we co-construct daily life. Some of these others are non-human, too. What is the mood and emotional underside of living democratically? How can we engage politically and openly in an everyday way with our neighbors?

Reasoning should be a loving relationship between people for moral reasons of who is doing the reasoning and how reasoning should fit into human flourishing. That we can quilt neighborhoods, if I may put it like like that, gives me some rational, human faith in this time.

What Else I’m Listening to/Reading/Watching

My Norwegian friend, Lars Helge-Strand, says I should be listening to microtonal music like Malmin. My kids like it, especially when the basement is filled with the neighbors' kids and everyone is painting.

Personally, I've been enjoying the gorgeous 2024 album by DIIV, Frog in Boiling Water. The songs are understated and then intricate, beautifully composed and layered, with thoughtful lyrics: "wasted all the commons/a looted golden calf/ivory towers and ivory crosses/my livelihood is rotting in your hand/man." They have come a long way from their earliest best beach rock of the 2010s.

And then Misty and I have been loving "Partly Fiction," which strikes me as a statement of great generation that shaped the edges of Hollywood and mainstream film. But, personally, the best single piece of film this year has been from Azazel Jacobs's mid-2000s, Good Times Kid, a piece of pure cinema like Gene Kelly singing in the rain.

What examples of relaxed street philosophy have you experienced? Examples might not seem academic at all, but on reflection, that was some philosophy going on there ....